When, some years ago, an editor commissioned a series for the re-telling of modern fairytales, I had a terrific time writing them, but I saved what I believed to be the best until last.

Little Red Riding Hood has to be one of the most famous of all children’s stories, as well as one of the most macabre. It’s woven itself into our folklore – it’s been told and re-told until it’s threadbare.

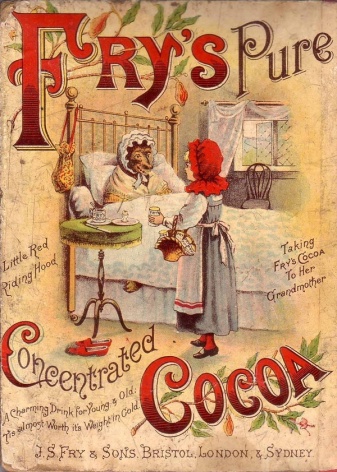

It’s been the subject of countless films and cartoons, and it even appeared in an advertisement in 1891, in which Red Riding Hood can be seen artlessly offering her grandmother a cup of Fry’s Cocoa.

It’s been the subject of countless films and cartoons, and it even appeared in an advertisement in 1891, in which Red Riding Hood can be seen artlessly offering her grandmother a cup of Fry’s Cocoa.

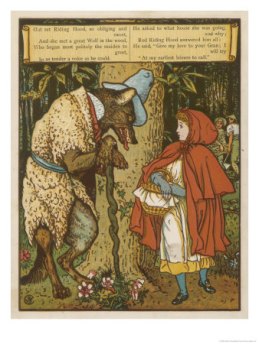

As a child I had a terror of that story, which I read by mistake, having found an ancient copy thrust into the back of a cupboard. The pages were dry and they smelled of age and forgotten memories. The illustrations (probably by Gustave Doré), were harrowing, but I read the story with a kind of horrified compulsion. Afterwards I had nightmares about wolves.

‘Oh, you don’t need to worry about wolves,’ said my practical mother, finally appealed to for reassurance. ‘There aren’t any in England nowadays. Henry VIII got rid of them all,’ she added cheerfully, as if she visualised Henry yomping across the countryside, personally routing every last wolf.

And yet, all those years later, nightmares and Henry Tudor aside, I discovered that a modern version of Little Red Riding Hood was the book I wanted to write. With the realisation, came the title. Wildwood.

The genesis of Wildwood’s setting came from an ancient Derbyshire legend, uncovered during a visit to a tiny place called Millers Dale. I thought, in a general way, that it would make a nice and appropriate background. But deeper investigation revealed the unsuspected, but intriguing, existence of the Foljambe family and led to the discovery of an unexpected and slightly disconcerting coincidence.

The Foljambes are documented in old Derbyshire records, and although the records are somewhat fragmentary, their provenance appears to be authentic. Little first-hand evidence of the family’s origins is available, but fascinating glimpses emerged during the searches.

The Foljambes are documented in old Derbyshire records, and although the records are somewhat fragmentary, their provenance appears to be authentic. Little first-hand evidence of the family’s origins is available, but fascinating glimpses emerged during the searches.

In the time of William the Conqueror (1066-1087), the Foljambes were enfeoffed as hereditary foresters. I do love that word enfeoffed even though I had to look it up to be sure of its meaning. It’s a 14th century word, from the Anglo-French, and Collins English Dictionary, probably one of the most used books on my shelves, has this to say about it:

[1] To invest a person with possession of a freehold estate in land

[2] In feudal society, to take someone into vassalage by giving a fee or fief in return for certain services.

So, the Foljambes were enfeoffed as hereditary foresters – a royal appointment which certainly included the slaying of wolves in the dense forests that covered a great part of the land.

The family was evidently successful in this part of its curious calling, since an entry in the Pipe Rolls of Henry II (1154-1189) refers to a sum of 25 shillings being paid to them as an extra fee for pursuing their profession over in Normandy – possibly at the request of the king.

In 1214 a Thomas Foljambe was knighted, and nearly a hundred years later, in 1301, Foljambe sons were summoned to the muster (which is another beautiful old expression, I think), at Berwick-upon-Tweed, to fight the Scots in the armies of the glittering Edward Plantagenet – the infamous battle in which the Stone of Destiny was seized from Scone Abbey by the English.

My enquiries and research indicated that the family had almost certainly died out when I wrote Wildwood. I did though – and I still do – tender my apologies to any descendants that might still be living today, for making so free with their history. But almost certainly they were wolf-hunters in the dense dark wildwoods that sprawled across the England of those years.

![41s4jr2396l[1]](https://sarahrayneblog.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/41s4jr2396l1.jpg?w=249&h=373) I loved writing Wildwood, my own version of this legend, and since its original UK publication, it’s been resurrected several times, in different versions, and in more than one language. In particular, German publishers issued it as Nachtwald, and with this title it’s recently been made available by Endeavour Media as an ebook, under the pseudonym I was using at that time – Frances Gordon.

I loved writing Wildwood, my own version of this legend, and since its original UK publication, it’s been resurrected several times, in different versions, and in more than one language. In particular, German publishers issued it as Nachtwald, and with this title it’s recently been made available by Endeavour Media as an ebook, under the pseudonym I was using at that time – Frances Gordon.

Here’s the link for ordering and downloading Nachtwald:

And for English readers, it’s still in English ebook format, published by Severn House:

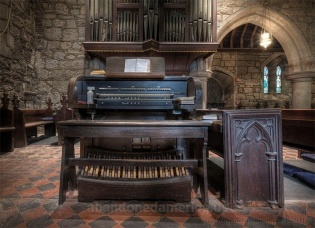

I explained the problem again. I wanted a church organ, abandoned for half a century in a desolate and eerie old church, to emit recognisable sounds when the village was re-opened. The organ itself would most likely be half-rotting, but it had to be still capable of creating music.

I explained the problem again. I wanted a church organ, abandoned for half a century in a desolate and eerie old church, to emit recognisable sounds when the village was re-opened. The organ itself would most likely be half-rotting, but it had to be still capable of creating music.

Over ninety years ago the German film-maker F.W. Murnau chilled cinema audiences with the 1922 silent movie, Nosferatu. It’s still chilling people today, and probably the creepiest scene of all is where the vampiric Count Orlok steals up the dark stairway, only his shadow visible on the wall. Thus sparking off a tradition that was to go from Hammer to Twilight, and provide a stream of starring roles for actors capable of turning on sinister charm at the drop of a garlic clove.

Over ninety years ago the German film-maker F.W. Murnau chilled cinema audiences with the 1922 silent movie, Nosferatu. It’s still chilling people today, and probably the creepiest scene of all is where the vampiric Count Orlok steals up the dark stairway, only his shadow visible on the wall. Thus sparking off a tradition that was to go from Hammer to Twilight, and provide a stream of starring roles for actors capable of turning on sinister charm at the drop of a garlic clove.

Translated into a warning to writers of pyschological thrillers, this oath might read: ‘Let there be no superfluity of splattering gore, no unnecessarily-festering corpses, no wild-eyed axe-killers or gibbering maniacs springing out of cupboards. Instead, let there be the midnight creak on the stair, the whisk of something sinister disappearing round a corner, a glimpse of the shirt-tail of a ghost rather than a glimpse of the ghost itself…’ And let the chills be understated, and let the reader’s own imagination fill in the blanks.

Translated into a warning to writers of pyschological thrillers, this oath might read: ‘Let there be no superfluity of splattering gore, no unnecessarily-festering corpses, no wild-eyed axe-killers or gibbering maniacs springing out of cupboards. Instead, let there be the midnight creak on the stair, the whisk of something sinister disappearing round a corner, a glimpse of the shirt-tail of a ghost rather than a glimpse of the ghost itself…’ And let the chills be understated, and let the reader’s own imagination fill in the blanks.